Who do we live for?

We live so that we—not anybody else—may die with minimal regrets. Yet, if the people around us would be a cause for regrets on our deathbeds, should we be living for them?

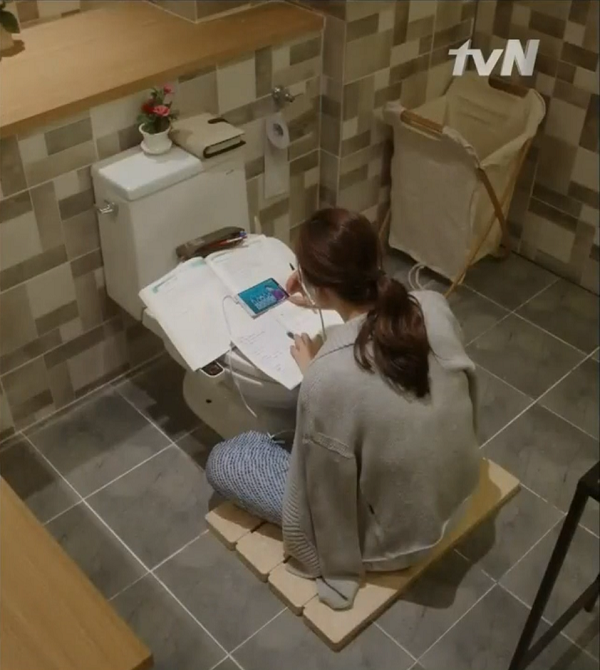

Twenty Again‘s 38-year-old, high-school dropout heroine, Ha No-ra, headed back to school in the hope that a college education could help her communicate with her snobbish professor husband, who was divorcing her. As the laws of drama universes would have it, she and her disdainful son were admitted to the same university, which her husband was transferring to as well. She narrowly avoided her husband’s class and made sure mother and son attended lectures on different sides of the campus, but unknowingly became coursemates with her son’s secret girlfriend and student to her husband’s mistress. The tension-filled reveals could wait, though, as her doctor delivered news of a more devastating disaster: her life would be over in six months’ time. More horror struck when she realized that she had squandered away her life while serving her ungrateful family and achieved nothing for herself.

What uplifted No-ra and gave new meaning to college life, even after she learnt that she was misdiagnosed, was a statement from Mozart a high-school secret admirer, now her professor, shared: “[D]eath is the key which unlocks the door to our true happiness.” Writing to his father upon hearing that the elder man was dying, Mozart remarked that death is the actual goal of human existence. Even as the possibility of his own abrupt demise was always on his mind, he found the idea of dying “very soothing and consoling!” Affirming this spirit of optimism, the drama explained that since our manners of death are important and how we die is the same as how we have lived, death gives us the impetus to live well, according to our own dreams.

A recent commentary pointed out, however, that had Mozart possessed a more serious temperament, he might have been troubled that his father’s demise, which really took place some weeks later, forever robbed him of the chance to fully repair their fractured relationship. Indeed, the two’s profound concern for each other, on the one hand, and conflicts over his character and struggle for independence, on the other, could be gleaned from the family letters. The writer sardonically wondered how the father’s death could possibly have unlocked the door to Mozart’s happiness. It is thus a reality that our lives and deaths intertwine with those of others, so much so that our goals cannot simply be about us and us alone.

At this point, it may be worthwhile to examine what living for others means. Strictly speaking, to the extent that we are acting out of free will, we are living according to our ideals and thus for ourselves. Hence, when we refer to lives in service of others, except under duress or other externally imposed obligations, we mean living according to self-defined/-chosen principles oriented towards others. In this light, people putting others before themselves are not weak or entirely lacking in dignity by default. Neither does the interference of the self make them hypocritical, since altruistic behavior arguably possesses higher moral worth when it is governed by the will, rather than by some uncontrollable forces.

A person feeling let down by unappreciative beneficiaries of his acts, though, is not living for them in any sense. This is unless it is their characters alone that displeases him, and he views the characters as ends in themselves. A rough means of gauging whether he meets this condition is to observe his reactions when the beneficiaries ignore or dismiss assistance offered by other parties. If he protests for himself but not for the others, even though the same efforts and results are involved, the condition has probably not been met. In rendering assistance to these beneficiaries, he is likely living for recognition and/or other recompense.

Now that we have seen how acts ostensibly benefiting others can indirectly serve the self, with or without having the others as actual end goals, are there instances when acts directly benefiting the self are necessary to secure the welfare of others? The issue of character comes into play again. People used to trampling over a benefactor or taking efforts of help for granted may develop self-entitled attitudes or, worse, seeing individuals like him as mere objects with no rights of their own. On the other hand, it is possible that the beneficiaries would be so touched by the unreserved assistance rendered they grow to emulate such selflessness. In this situation, they may be the ones who need a reminder to assert their own rights lest they become tools of exploitation. Still, the benefactor may do well to take care of himself so that he will have the ability to take care of them. Moreover, over-reliance on him may thwart the beneficiaries’ development of survival skills that will be essential when he is unavailable. For the betterment of her family and for protection of women like herself, No-ra, for instance, should have insisted that they treat her with respect and carved out a life of her own even before she faced her own mortality. From such perspectives, living for the self can be an important subset of living for others, just as the reverse has been true.

We are now left with the weighty question of whether our highest ideals, insofar as they involve people, should concern others or ourselves. The best approach would be a win-win strategy, whereby we safeguard both our interests and those of others. When this is impossible, though, whose interests do we work for? A cardinal rule most people would probably agree is that there are some interests of others that are so fundamental (e.g. rights to life, basic health and physical/mental integrity) they should never be violated to further our own interests. Exceptions for self-defense may be permissible, but these mainly concern contingent scenarios separate from the general attitudes towards life planning under discussion here. A secondary guideline would perhaps be that, if we only need to sacrifice a reasonably small amount of our interests to advance others’, we should not be so self-absorbed and miserly as to refuse to give a helping hand.

In matters where these rules are inapplicable, there is more room for maneuver, but also more shades of gray. Should a single mother relocate for a more intellectually stimulating job in a city which offers poorer (but not abysmal) educational prospects for her child? Should Mozart have lived less in the moment and more for the (sometimes capricious) future to put his father’s mind at ease? In an introduction to his novel The Alchemist, Paulo Coelho wrote that people who truly care for us would want us to be happy and give our ambitions their blessings. Some commentators, too, painted Mozart’s father as a power-hungry man in his intrusions into his son’s affairs. Yet, if it is moral worth that dictates whether a person deserves to be lived for, are those who forsake his happiness really any more deserving? Furthermore, it could be that different individuals speculate about someone’s long-term happiness in different ways, and each cannot be persuaded otherwise. Time will tell who is right, but certain decisions are irreversible. And sometimes, death descends before all the consequences play out.

Perhaps, the choice between one individual’s self-fulfilling destiny and another’s is too intimate a matter in the absence of overt ethical transgressions for an outsider to play God. We can advise each other but everyone and his potential beneficiaries may have to negotiate and ultimately decide on their own which ideals to adopt. This is where “we” is giving way to “I.” On a macro level, it is only hoped that the decisions taken will be the ones that open up the most possibilities and factor in considerations of the greatest certainties. Depending on personal values and family/cultural beliefs, though, some probabilities can carry greater weight than certain absolute certainties.

Whichever route we choose, there can be beauty in both the fulfillment of personal destiny and the participation in a warm, ethereal world where benevolent souls generously nourish each other, in the style of the well-known “allegory of the long spoons.” If one’s destiny would always lead to that world and if that world holds one’s destiny, he may indeed draw his last breath in perfect peace. In the absence of this luxury, though, we may still have to live life to the fullest in the direction we take, so that the sacrifices left behind would at least not be in vain.

Special thanks to the following bloggers for their expression of support in the prelude to this post:

Blue

Blue

Wow – There is so much here to ponder! Excellent, thought-provoking post, as usual! I could picture so many relationships that could be represented in this situation, so many people who devote their time and energy to someone who does not or is not able to reciprocate the same. As you said, sometimes it can be a selfless act of love that is meaningful and fulfilling despite not getting the same treatment in return. Other times it is a lesson in futility, and you find yourself wondering why that person stays in the one-sided relationship. I’ve also witnessed ironic situations where one person changes themselves to be what they THINK the other person wants, meanwhile the other person wanted the person they fell in love with, not the overly-accomodating version they ended up with. Love is indeed a mystifyingly complex thing! But I agree with the idea that being with someone who appreciates you for who you are (and visa-versa) leaves so many paths open for discovering happiness and meaning in this world and less regrets at death.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, as always! The way you look at the world is rather beautiful. I wish I can emulate that. The point about people upset about their spouses becoming overly-accommodating was raised in Twenty Again too, although it DEFINITELY does not justify infidelity. I think it applies to the workplace and even blogosphere too. Sometimes, honest comments are not very well-received. But there are also times when people wish those around them can be their genuine selves, instead of bending over backwards to be diplomatic.

I’m curious about everyone’s thoughts about the dilemma mentioned towards the end of the post: assuming that there is no way of mitigating the (non-grievous) harm of a certain act to another party, is there one side you are more inclined to support: the decision maker or the other person? Should the answer differ depending on whether that other person is his/her parent or child? *Deep in thought*

That’s a tough question for me, because at this point in my life the only person I have truly made great sacrifices for is my child. Whether we think of ourselves and our own happiness before the happiness and needs of others might then depend on the relationship. When denying your own happiness and fulfillment for your child, I think it falls into that “matter of principle” or “higher moral worth” you spoke of. There can be more thought of “self” when the decision affects another adult, like in a husband/wife relationship.

As far as who I am more likely to support – the decision maker or the other person? I guess it depends on the situation. The husband’s decision to divorce mIght seem cruel after all his wife has done for him, but would staying together be worse for both? Would he just end up resenting her more if they stayed together? In this case, his decision to divorce may be the impetus for her to find herself and be able to lead a fulfilled, happy life. And although I would sympathize with her pain at first, if she continued to sacrifice her happiness for a failed relationship, wouldn’t she end up complicit in her own misery?

Another thought: It would be interesting to see if her son would actually treat her with more respect if she left and created a life for herself. Maybe he holds resentment for her inaction and lack of self-respect.

Indeed, her son has started to think better of her in the latest episodes! I guess while it’s meaningful to ponder about theoretical scenarios where one party is bound to suffer, we shouldn’t give up too easily on win-win solutions. A female Korean-American professor said that all six of her children became university professors as well because she “walk[ed] the walk, rather than just talk[ed] the talk.” Her children always saw their parents studying and followed suit, even though they were never told to do that. Their home was like a small library and NINE desks lined the walls. Even the kids’ friends would end up studying when they visited the house.

(Sources: http://www.koreana.or.kr/months/news_view.asp?b_idx=1145&lang=en&page_type=list, http://www.nhregister.com/general-news/20090327/mom-thrilled-by-sons-nominations)

I fully support the divorce in the drama too. To his credit, No-ra’s husband is a rather hands-on dad [Update: in the current timeline], unlike some dads you see around, and works hard at his job. He probably even loves No-ra more than the mistress although he may not realize this. It’s just that the person who’s out of reach tends to be more alluring than the one you already have. Oh well, too bad for cheaters.

Sounds like a really interesting show! I like when characters have depth, like when the writers give us, the viewers, a chance to see the human side of a character who is meant to be a villain. It makes the story more complex and thought-provoking.

What a great story about the Korean-American professor! 🙂