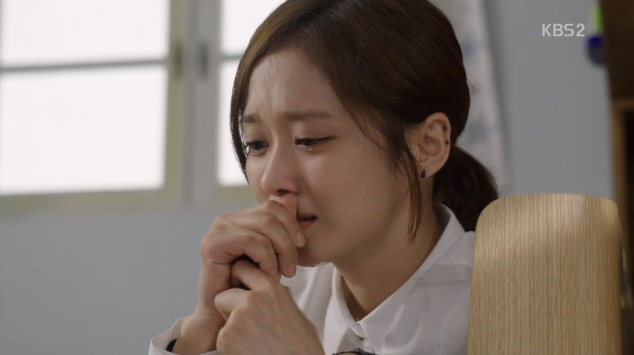

The term “caring psychopath” seems to be an oxymoron, yet Hello Monster‘s archvillain, Lee Joon-young, appeared just that. The serial killer attempted to change the course of destiny for many people he met for the better, except that, tried as he might with his extraordinary intellect, he could not comprehend the human psyche. Registering the heroine’s dislike of ambiguity in a conversation on her family, he decided to end some cruelty he inadvertently inflicted on her with a well-meaning birthday gift: the bones of her father, a missing guard whom he murdered without the knowledge of anyone more than 20 years ago during a prison escape. She flew into a tremendous rage, to his befuddlement, and had to be stopped from storming into his house with a revolver.

It does not take a psychopath, though, to mercilessly extinguish hope in clinical settings. By deprioritizing life-saving treatments, by presenting grim statistics without adding the caveat that they are no definitive statements on any individual’s exact fate, and by addressing patients in an unnervingly solemn tone, physicians can destroy people’s will to fight for their lives. Conversely, however, by enthusiastically placing terminally ill individuals on one treatment plan after another, notwithstanding low likelihoods of success, and putting a positive spin on bleak prognoses, physicians can also induce patients to undergo unpleasant and time-wasting therapies, set them up for greater disappointment and divert attention and energy away from activities that can make the last stages of their lives more meaningful (e.g. fulfillment of remaining dreams, family bonding, etc.). Both hope and hopelessness, when out of sync with reality, can backfire.

In contrast to outright deception, false hope and false hopelessness need not always involve actual concealment of truths or deliberate manipulation. Clinicians may merely be nudging patients to focus on some potential scenarios, while the remaining range of possibilities lie in plain view. In certain instances, they may consciously or unconsciously employ language or gestures suggestive of, but not restricted to, a particular interpretation. In yet other cases, misunderstandings arise due to a lack of scientific literacy on the part of patients, as the above example on statistics demonstrates. Doctors themselves, though, are not immune to unfounded hope and hopelessness either. Being human, they, too, may interpret past success rates and disease progress in their own, biased ways, with some believing that their superior medical skills will make them exceptions to dismal trends. Thus, they mislead patients sometimes because they have misled themselves. Even when everyone is capable of objective judgment, some may intentionally harbor or abandon hope because of the inherent value or dangers of the feeling. Since the pitfalls of outright deception have been discussed elsewhere, this article will concentrate on these additional issues implicated in false hope/hopelessness.

First, to cut through clutters of vague talk and delusional signals and see reality as it is, there needs to be a culture of fearless and relentless questioning by patients. This calls for approachable medical practitioners and a healthcare system that allows more face time and convenient communication channels between patients and practitioners. Far from perceiving verbalized doubts as threats to their authority, physicians must be willing to question their own assumptions and admit the limits of their knowledge and capabilities. That would naturally cover the limitations of statistical analyses. It is critical, however, that all these occur without sliding into fatalism and while maintaining mutually respectful attitudes.

What might be helpful as well is a more open, fluid and diverse medical climate, so that patients find it easy to seek second (and even third/fourth/fifth) opinions. Regrettably, a number of barriers are standing in the way. Some physicians, for example, may interpret the search for alternate opinions as distrust of their expertise. Hence, when word of such patient activities spreads through the grapevine, patient-doctor relationships can become fraught, impeding cooperation between the two sides in future diagnoses and therapies. Colleagues, additionally, may be reluctant to cast doubt on opinions by veteran practitioners. In the United States, there are also insurers who refuse to pay for alternate opinions. Still, these could have been less of a problem for educated and technology savvy patients in the Google age, if not for paywalls restricting access to journals with information on the latest epidemiological data and treatment outcomes.

Again, attitudinal shifts would probably facilitate the breakdown of those barriers. One of these shifts would be in having more doctors see dissenting practitioners not as challengers to their positions but as peers to study from and test their skills against. In reality too, mortality rates and quality-of-life outcomes are arguably more significant measurements of professional competence than patient retention rates. As long as physicians keep upgrading themselves and perform better in these areas than fellow professionals with conflicting views, there should be little need to fear such views. Insurers can help out by viewing the clarification of medical conditions through rediagnoses as cost-saving opportunities, rather than wasteful expenditure. A large-scale study, in fact, has found that around 60% of second opinions differ from the results of initial consultations. Healthcare institutions also have a role to play by opening up more learning centers stocked with the latest medical references, including subscriptions to electronic journals, with the warning that patients should not use them as substitutes for clinical examinations.

With clear communication and objective evaluations in place (to the extent that they are humanly possible), physicians would be left with the issue of whether to moderate any disproportionate hope or hopelessness that patients willfully cling on to. Currently, when a patient’s emotional state affects his medical decisions, laws in various jurisdictions govern how clinicians may react. To begin with, doctors are often exempted from providing treatment they deem immoral or against the patient’s medical needs. At most, they have a duty to refer him to practitioners accepting his view. On the other side of the fence, mentally competent patients reserve the right to refuse treatment, even when doing so will lead to death. Although imperfections may exist, rightful steps have generally been taken toward a balance between physicians’ freedom of conscience and patients’ bodily autonomy.

The management of patients’ mental autonomy may be more challenging. When despair slips into depression or other mental disorders and the affected persons pose threats to themselves and/or others, they can be compulsorily subjected to psychiatric treatment under various legal provisions. Nonetheless, even without such threats, physicians have the freedom to coax or remonstrate with patients to change their thinking. Yet, stripped of its physical and psychiatric consequences, can hope or the lack of it be objectively wrong? What alternate viewpoints should inform the lengths doctors go to influence patients?

In essence, hope is a feeling that something positive or desired exists or can come true. The word “can” has significance that goes beyond logic. More than a placebo device and anodyne, hope is an embodiment of one’s values. Most notably, a hopeful person may regard himself as an indefatigable and valorous warrior. However dim a chance is, it is always worth fighting for. Although the outcome may break his heart, it is just as likely that, had he not harbored the hope, he would die feeling disappointed in his cowardice and wondering if a miracle could have occurred if he had tried.

An acute observer would also note that that overarching definition of hope is loose enough that it is not really tied to any particular outcome. The problem in medicine is that people frequently associate hope only with recovery. Yet there are other positive and desirable experiences worth looking forward to at the brink of death. Having undergone intense suffering and faced the prospect of losing everything, patients can offer those around them sagely advice on how best to lead their lives and cope with adversities. To clinicians, they can even become reverse mentors on the needs and inner worlds of dying patients. In light of such possibilities, The New York Times has highlighted the importance of reconceptualizing, rather than abandoning, hope.

Even the most tired and feeble dying patient can find something precious in hope. To someone in a bottomless chasm, hope is a golden sentiment of pure kindness. There is nothing more it asks for than a kind of gentleness, nothing ravenous or iniquitous in its inherent nature. Precisely because the circumstances it is created in are desolate, it feels all the more ethereal and softly divine, wherever it leads. Not everyone will agree with this view, but who are the others to tell a dying person who does that this silent beauty does not exist?

On the flip side, there are those who prefer seeking purity in rational thought. To them, it is more important to retain a clear-eyed view of the facts and approach the future with stoicism, neither awash with joy nor mired in useless sorrow. Aristotle claimed that hope is “the dream of a waking man,” a quote Lee Joon-young cited during the Hello Monster conversation mentioned above. They, however, may think that a dream has to be ending for waking to be truthfully probable. Friedrich Nietzsche, interpreting the retention of hope in Pandora’s box (which was really a jar) as the box gifter’s intention that Man foolishly endures the (other) evils unleashed, declared hope “the worst of all evils,” another quotation Lee Joon-young proffered. While similarly disavowing hope, they would probably reject the automatic assumption of evil as well and question the relevance of ancient myths to modern-day reality, choosing instead to simply make the best of what they have. The ability to do these may actually be their unique version of hope.

Doctors are not saints, yet they are frequently held to saint-like standards and placed on a pedestal. There is immense pressure but also immense meaning living under such expectations. A gentle reminder everyone can perhaps benefit from, though, is that even true saints may need to step out of their shells, explore around and envisage different kinds of heavens to serve the erratic needs of a diverse populace. Sometimes, the heaven may have to be built within a forlorn hell. We cannot put an absolute value on hope/hopelessness, just as we cannot readily label a child with eccentric cognitive behavior as a monster in the making, in case we restrict their potential and have both grow into real, helplessly unempathetic monsters.

I was puzzling over a similar paradox in Breaking Bad, how a person so sociopathic can nevertheless seem to care for some people. But then I realized that WW doesn’t care for them so much as people as he cares for them as his possessions.

There’s hope(?), though: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fulfillment-any-age/201305/despite-popular-opinion-psychopaths-can-show-they-care !

Maybe that’s the difference between a psychopath and a sociopath? I will have to think about it …

Will the hot-headed but less calculating sociopath be easier to control? Or the more emotionally stable psychopath? That’s food for thought!

Lee Joon-young tries to change people’s destinies because he would have liked to change his own. He sees himself in most of those he helps: the person he was (victims of abuse), the person he is (a full-fledged psychopath, i.e. Lee Hyun’s brother) and the person he would have wanted to be (a genius who’s merely eccentric, i.e. Lee Hyun). There’s also one case where the other party is his benefactor in a small but important way (his knowledge of Nietzsche may very well have come from the books she brought him!). Cha Ji-an is probably the only one he is helping not for his own sake, which may be another reason why he’s stunned and maybe a little anguished when she seethes with anger.

Such a wonderful article analyzing the many aspects of hope and hopelessness and the driving forces behind them. It truly is amazing how such seemingly simple emotions can completely alter the course of people’s lives.

It really makes me interested in checking out Hello Monster too!

Do check it out! It’s a little bit slow for me but the theme, uncluttered scenes, bromance, geeky references and steady relationship between the leads work in an understated way. I also wonder if the production team has been deliberately selecting geometric and semi-MC-Escherish motifs for the shooting locations. And it certainly helps that its logic is far much stronger than those of some prominent crime-related K-dramas broadcast this year.