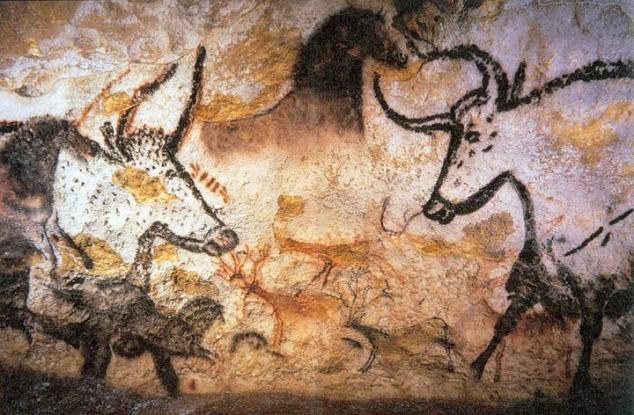

Paleolithic cave painting in France, © Prof saxx, shared under the permission of CC BY-SA 3.0.

Can courage in its purest form, detached from all worldly wants and messy emotions, indubitably produce the purest good?

Epic blockbuster The Legend has mighty ambition written all over it. Not only does it depict the story of 4th-5th century Goguryeo king Gwanggaeto the Great, whose conquests led him to reign over the largest territory in Korean history, through grand battle scenes, it mixes in the founding myth of Korea, Christian symbolism, an artistic sensibility reminiscent of medieval European legends, and the Four Spirits of Chinese astrology portrayed in Goguryeo murals: the Black Tortoise of the North, the Azure Dragon of the East, the Vermilion Bird of the South and the White Tiger of the West. In the drama, the Black Tortoise totem is activated when Gwanggaeto experiences dark fury, the Azure Dragon totem in times of cool benevolence and the Vermilion Bird totem in burning passion. The White Tiger totem is the one representing innocent courage and the divine creature is reincarnated as Jumuchi, a tribal warrior of Herculean build who fights for righteous causes without a tremble and without care for material gains or bodily well-being.

Yet it is often claimed that courage is not the absence of weakness, but the willingness to act despite weaknesses. In the third episode, an insecure young Gwanggaeto is indeed advised that courage is not without fear, but acting in spite of fear. Nevertheless, language is a matter of conventions, and no commentator is entitled to disregard one set of conventions in favor of another. If courage has been widely associated with spiritual resilience, this other meaning of the term ought to be acknowledged too. Arguably, a more complete definition of the term is the willingness or ability to face danger, pain and/or fear, which may or may not involve acting in spite of them.

The Legend‘s filming set, © Thddbwnd, shared under the permission of CC BY-SA 3.0.

Still, it is possible to speak of different “species” of courage, and emotional susceptibility could be one determinant of their relative worth. Instinctually, the difficulty of the obstacles influences how admirable a quality or act is. To be consistent with this judgement criterion, someone immune to sensations of horror and anxiety would sadly have to be ruled out as a paragon of noble courage. He might have plenty of company, though. Individuals capable of experiencing pain and fear may still be immune to common objects of pain and fear such as embarrassment, ridicule and sense of duty. Or they may simply close an eye to details, including potential consequences of their decisions.

This issue of consequences, in fact, probably deserves more attention in popular conceptions of courage. The mention of “courage” likely conjures up images of hero(ine)s either bracing for impending calamity or in the thick of action. Yet what is to say of those crumbling only after the dust has settled? There is nothing in the definition that exempts the forbearance of pain even then. Seen in this light, as long as the individual retains emotional sensitivity, the battle is not yet over.

If there is little concern about post-incident courage, the reason may be a perceived lack of practical difference courage can make when all is said and done. But if a person were to fend off upsetting emotions after reading the above paragraph, his motivator might not be the difference it could indeed make—getting back on his feet and securing mental wellness—but rather the desire to live up to an ideal of courageousness. Indeed, it can be speculated that this desire also powers many (but not necessarily most) ordinary acts of courage. In other words, behind courage possibly lurks the fear of being uncourageous. From this perspective, courage and cowardice are often one and the same. In such situations, one is really choosing between two forms of courage: the courage to do what courage conventionally demands and the courage to forsake conventional courage.

Not everyone struggles with both types of courage on every occasion. Perhaps, a person just wants to act with whatever courage that is right for a given situation. But that retort would not automatically chase away some meddling philosopher as it begs the question of whether courage itself can be unfailingly right. Should not the value of the willingness to do something or an ability depend on the purpose it serves? The “courage” to murder and plunder surely cannot be sanctioned. In the case of post-incident distress, too, even if the individual would have no difficulty ignoring conventional wisdom and thus no courage to forfeit conventional courage to speak of (recall the danger/pain/fear definition of courage), only conventional courage as a potential goal of resilience-building, there is still the argument that he may need some space to release pent-up emotions. Moving on straightaway with courageous stoicism may not be the wisest choice.

The positive connotation of the noun “courage” does suggest that it is intended for a beneficial and ethically unproblematic end. Nonetheless, that does not prevent misuse of the word or similar terms like “bravery” and “fortitude.” It does not prevent injudicious acts pursued in the name of “boldness,” “guts,” “fearlessness” and more either. In this age of terrorism, in particular, we see rhetoric about not being “cowed” by threats of violence, not being “overawed” by barbarism, and not “backing down” paraded around. Here, it is perhaps only realistic to emphasize the image of strength and fearlessness to the enemies. A problem can occur, though, when those ideals are literally taken to mean living life as usual, leaving the populace open to more attacks from terrorist groups, which its unchanged pattern of living may starve of only some emotional gratification. The possibility that the relish of the carnage may be sufficient incentive to repeat the violence seems hard to rule out. Contrary to what some critics claimed, it remains to be examined whether courageous adherence to the normal mode of life is truly more important than cumbersome (but much preferably, respectful, non-discriminatory and proportionate) security countermeasures minimizing future casualties.

Overall, though, the world most likely can do with a great deal more courage for its innumerable problems. It is just that, no matter the awe the quality induces, the true goals should not be courage per se, and taunts of cowardice should not be the motivation for action. In the event that the less dignified and, perhaps, duller option would be the one that does more good, we probably have to pursue and uphold it with as much passion as we pursue courage.

Jumuchi, a tribal leader of the Mohe people

Special thanks to the following bloggers for their expression of support in the prelude to this post: Freda @ Aromatic essence

Freda @ Aromatic essence Cindy Knoke

Cindy Knoke Tasty Eats Ronit Penso

Tasty Eats Ronit Penso Kay

Kay

–

–

–

–

Is this about the 2007 Korean drama? I only remember what it was about roughly but the idea explored here is interesting! I should go watch it again sometime 😀

Yup, the 2007 Yonsama drama! I love the mythology and childhood episodes.

Yes! I remember liking the myths behind it as well 🙂 As for the childhood memories, I’ll have to refresh my memory first :b